(Letzte Bearbeitung / last updated on 09/03/2025)

The following interview with Ruth Veit, née Koch, dates from 2011. It was conducted in the presence of her family and recorded as a video. Ruth’s grandson-in-law Daniel asked the questions. Her husband Sigi and her children Barry and Debra were also present during the talk. Ruth Veit was 86 years old at the time of the recording. The original video can be found here and was made available to me as a copy by her daughter Debra during my visit to Chicago in October 2024.

Can you please say your name?

My name is Ruth Veit. V – E – I – T.

And you were born with what name?

Koch. K – O – C – H, typical German name.

And what year were you born?

1925, May 15th.

And in what town were you born?

Alzey. I was born in Alzey. It used to be a two hour train ride from Frankfurt. You had to change trains, because it’s a very small town. About 10, 12.000 inhabitants.

And your parents’ names?

Erna and Otto Koch.

Do you have siblings?

I have a sister that’s 18 months older than I am. She lives in Florida.

What’s her name?

Her name was Lieselotte, and it’s Lila now.

And what was your childhood like?

My childhood was more or less normal. But my mother died when I was a year and a half old. And so we two children went to both of our grandparents. My father lived in the same house in his apartment in Alzey, in a small town, and so his parents. My grandmother cooked. She took care of us. We played with our father and plenty of children. When we were with our other grandparents, that was in Groß-Gerau, that was near Darmstadt. We had a very nice childhood. We were more with my mother’s parents. They had a nanny for us because that was how it was done in those days.

Were you guys a close family growing up?

Oh yes, oh yes. But then in 1933, the Nazis came and beat up my grandfather, my maternal father, during the night and extorted money.2This happened on the night of March 31 to April 1, 1933, when the National Socialists attacked Jewish stores across the country and called for a boycott. SA members were also posted in front of the shops to record and intimidate all customers. So they knew they had to leave the little town and we moved to Frankfurt, where we could go to a Jewish school. And life was good, was normal. At the beginning, we did not know about the Nazism as bad until that time as the years went on.

Was that the first experience of Nazism?

In 1933, ’34. Then it was fairly normal until maybe ’36, ’37. And when we went to school, we went in rows of two girls, walked together because we were afraid. Once we were beaten up from just some bad boys. But it was nothing too bad. We could go back to school a day or two later. Life was good.

What did your family do for a living?

My grandfather had a business everything pertaining to building a house, bricks, tiles, and bathroom fixtures, sinks, coal, wood, because in those days you had open stoves to heat. My father was in business with his father. That was corn, wheat, dry flour, wholesale in big sacks, burlap sacks.

Produce or manufacturing?

No. I don’t know. He would fill up the burlap containers. It came in big quantities, but my father and my grandfather filled it in burlap containers, and it would be sold to the farmers.

And your father and grandfather’s name?

My grandfather was Ludwig Koch. My father’s name was Otto Koch.

And your other grandparents name?

My grandmother on the Koch side, her name was Thekla. My mother’s parents, their name was Adolf and Settchen Guckenheimer.

And you spent the majority of your childhood with them?

With my mother’s parents. But vacations and long weekends, we would go to our father’s house, back in Alzey, because we could not go to school there. We needed a Jewish school.

What was your social class? Where you comfortable? Where you middle class, lower class, upper class?

My father and his parents were, I would say, comfortable. Up until the time they traded on a market in a big town. What was it called?

Exchange.

Exchange. They couldn’t do that after, I don’t know what year it was, maybe ’35, so they could not make money on that. So they strictly depended on the farmers who came. A lot of them were not supposed to come because you shouldn’t be buying from a Jew. Then money went down fast, they were not wealthy. My other grandparents, however, they sold their business in Groß-Gerau, and they were, I would say, quite well to do.

Now, let’s talk about the school. Where did you go to school growing up?

In Frankfurt.

And the name of that school?

The first one was Philanthropin. That was a public school, from age ten, maybe. No, I was younger. Eight, nine, thereabouts. I was not a very good student there. There were about 25 children in a classroom. So I was sent to a private school, where my mother went, where my grandmother went.3This is the “Dr. Heinemann’sche Mädchenpensionat”, a private Jewish school at Mendelssohnstr. 84 in Frankfurt’s Westend district. There you had very few children. And you learned a lot better and you couldn’t move off.

(Ruth Koch is the 6th from the left in the back row.)

And how long did you stay in school?

I stayed in school until I was thirteen.

Did you realize some anti-Semitism?

Just one time when we walked home. We were very shielded in those days. Our grandfather, he would come halfway, he would look out for us. And we walked. The walk to school was a good twenty minutes, half an hour. But in those days, you didn’t get picked up from a bus. You walk, but you always had to walk with another girl.

Did you go or attend any Hebrew school?

Yes, in Frankfurt, we went to a synagogue. We learned a little. But when we went to the small town where my father lived, there we went to the rabbis house in the afternoon, and we were taught there.

Was your family a member of any synagogue or congregation?

Anybody belong to a temple, yes. And we had to go every Schabbes morning.4“Schabbes” is the Yiddish word for Sabbath. We were not religious. We did not keep a kosher house in Frankfurt. My grandparents were very liberal. They did not eat pork or anything like that. But if my grandfather would want a piece of liver sausage, he would have to eat it out of a paper. He could not use a plate. In Alzey, my grandparents, they were more religious. You got your meat from a so-called kosher butcher, but they couldn’t kill, in those days, the kosher style anymore. So when the meat arrived, my grandmother would kosher it herself two hours in water and one hour in salt or vice versa. I don’t know exactly. And she imagined it was kosher.

When did you realize that your life as you knew it was going to change?

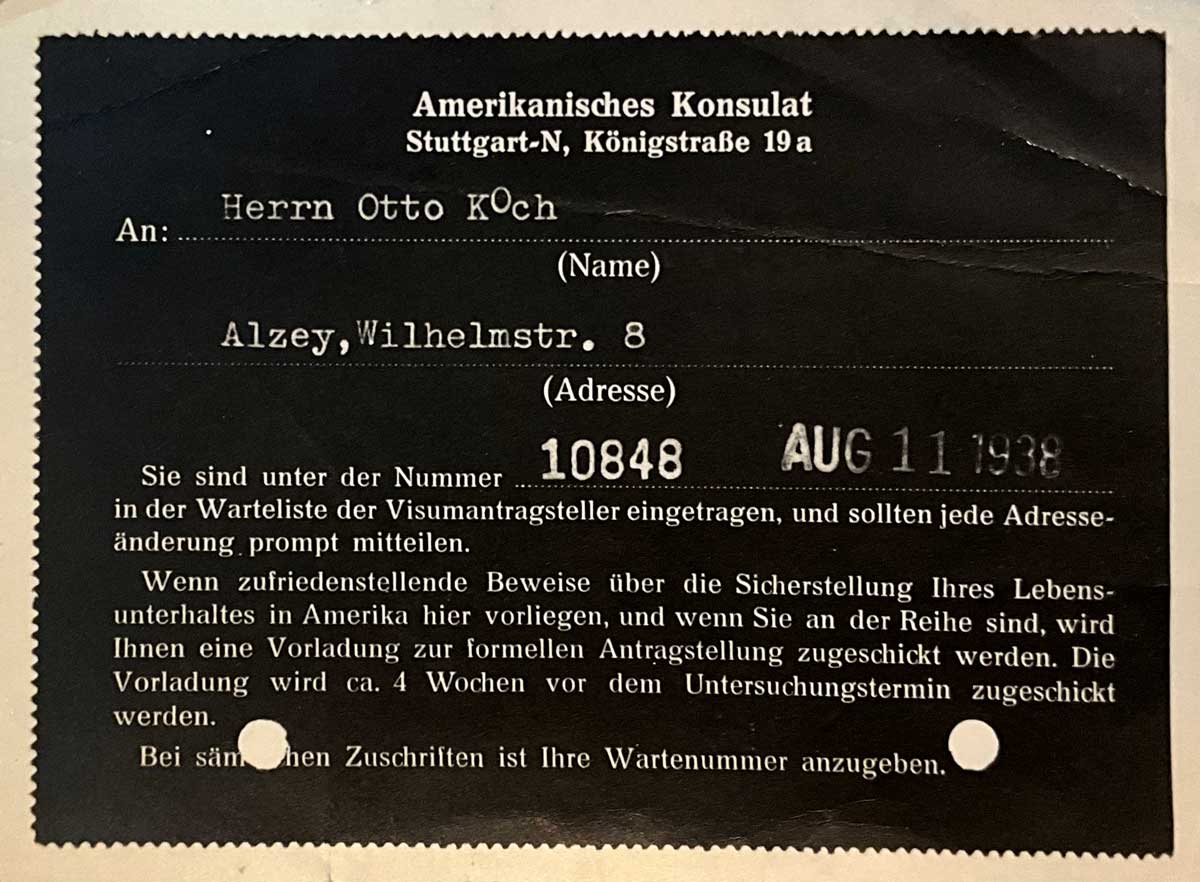

We could see in store windows. We couldn’t go to the movies. There were signs „Juden unerwünscht“ – „No Jews allowed“. You couldn’t go to a zoo or any entertainment. You couldn’t do lots of things. And we as children, our grandparents tried to shield us and not tell us everything about it. But you could feel it and you knew how far you could go. And if there was anything unusual in the street, you just walk past it and you come home. A lot of people emigrated. My father decided he was going to go to America. And he talked to my grandfather and he said he’s willing to go and take one child. My sister was the older one. And as soon as he gets to America, he will find an apartment for the rest of us and we will follow . You had to have a number. You had to write to an American consulate in Stuttgart. And I still have his ticket with his number on it.

Well, you mentioned your dad that he applied for a number at the consulate to come to America. But he never came to pass because, we have to tell about that, he was arrested. And he never came back. He was arrested and taken to concentration camp…

Then, one day, an ordinary day, 9th of November, I went to school in the morning. And I was hardly started, when a mother came, she was still wearing her apron, came running in to grab her two children, a boy and a girl, twins, saying, „All of the synagogues are burning.“

Teacher didn’t know about it. And they said we could all go home. We had to go with a friend. We should not walk alone. We went home. My grandparents didn’t know a thing about it.

And my grandfather, he was the strong one in the house. He said, we’re going to go to Wiesbaden, where a sister-in-law lived. She was a widow.5This refers to Rosa Guckenheimer, the wife of Adolf Guckenheimer’s brother Ludwig Guckenheimer, who died in San Remo in 1937.

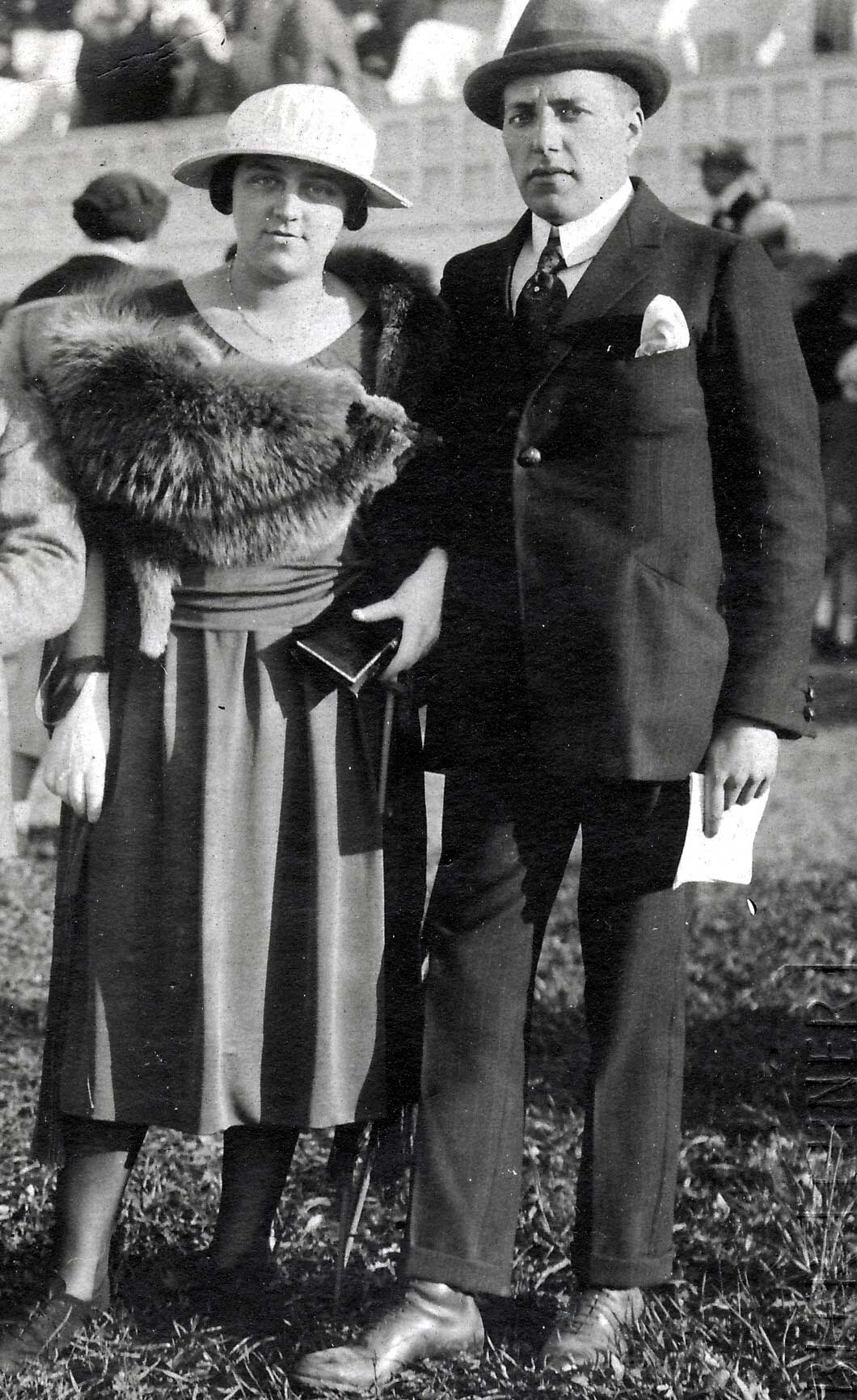

Rosa and Ludwig Guckenheimer, ca. 1936 So they didn’t have to be afraid that a man would be picked up. Our maid, my grandmother and sister left to go to the train station.

And my grandfather and me, he worked on some papers and he went in the basement where there was a coal bucket. There were buckets full of coal to heat the heater, and he put money in there. And then he filled it up with coal. He put some things on him and we left without a suitcase, just as we were, so that we should not look suspicious. We also went to the train station and took the first train to Wiesbaden, which wasn’t far, maybe an hour.

And waited there for a couple of days until things quieted down. But we heard that every synagogue was burned down in the whole country. We, of course, called our father, I don’t remember how that was, but we heard my grandmother in Alzey, my father’s mother, answered to tell us. Our father and grandfather were picked up and they walked around the village with a shield on them. „Ich bin ein Saujud“, which means „I am a pig of a Jew“. They walked around. And in the evening, they were injailed.

Next morning, my grandfather, I believe he was in the sixties, he was released – went home. My father, they kept, he went to one or two camps, sort of a stop, before he was finally shipped to Buchenwald, which was a concentration camp. And he got there, I don’t know which day, but he was taken on the 9th of November.

A few days before he came home we went to the police. My grandmother, my sister and me, my father’s mother, my sister and I, we went to the police station. He earned the Iron Cross in World War I. He was in the army, whatever rank, I don’t know, but he won the Iron Cross so we figured this might be, they will release him. The police officer said we will see, he will be home on Thursday.

Thursday came and what we got was a box, a wash powder box, like here they have a tide box, or whatever brand you want. There in Germany it was called “Persil”, and in that box were his ashes. I was thirteen.

My grandmother and grandparents didn’t know what to do. But my father had a friend living in Worms, which is a bigger city not far, who was a rabbi. He came. All men’s heads were shaven as soon as they got to the concentration camp. They were stripped of all their belongings. He came to conduct a funeral.

We were not allowed to get. There were no grave diggers to help us. My grandparents buried him in my uncle’s grave.6This refers to Uncle Emil Liebmann, the husband of grandfather Ludwig Koch’s sister Laura. My uncle has a big grave with a headstone. He lived in Alzey also. He died long before my father. We opened up the front of his plot and put his ashes in there and have it inscribed in the same headstone as my uncle.

And you have a picture of that?

Yes, we have a picture of that. When our father died, I said his friend came to conduct the service. We stayed at my grandparents’ house which was – not „distorted“, the word is not „distorted“. The whole apartment, it was a mess. Pictures, oil paintings were cut with a knife. Furniture, upholstered furniture was cut. They just ruined everything. If they saw in the buffet good dishes, they just took them out and then threw them on the floor. The apartment was completely disheveled and my grandparents, as you can imagine, my father had just died. My grandfather came back after being held by Nazis overnight. They were distraught.

Was he beaten also, your grandfather?

I don’t remember that.

So he was released from jail and he returned home to his apartment?

Yes. But I lived in Frankfurt, it was during the school year. This went on in Alzey on the 10th of November. That’s when they were taken. And when we heard in 8th of December, our grandmother called that she just had news, that he died. We were in Alzey quite a bit because we were hoping we could get him released from Buchenwald. We did go to the police with his Iron Cross, but they said he would come home Thursday. And after the funeral, I don’t remember how long we stayed in Alzey. I don’t remember whether we said „Shiva“.7„Shiva” means „seven“ in Hebrew and stands for the time of mourning in the first week immediately after the funeral of a close family member. I don’t remember that. They were hard times.

And how much longer did you stay in Frankfurt?

My grandparents thought it’s best to write letters to family for an affidavit8„Affidavit“ is a notarized declaration of surety that enabled persecuted persons to enter the USA. to come to America. I read about close to 90 letters that my grandparents sent to America. I got them all begging for an affidavit, and no one could furnish one. My sister got one. She was young. She was able to walk. And I think people were afraid that my grandfather, who was quite spoiled and wealthy, could not earn money to keep himself, or that he might be a burden. I really, I don’t know. But they did not get an affidavit. My other grandparents, my father’s parents, ran out of means to live. They went to a Jewish old age home in Mainz. The town is nearby, but it’s a bigger town, where they had still Jews living, and they went to that old age home. By that time I had already left for England.

And what year did you leave for England?

I left in ’39, March of ’39.

Who made the arrangements to get you?

Our grandmother, Guckenheimer, my mother’s mother.

How old were you?

I was thirteen. My grandfather was so against it, without saying I was his favorite. I was the younger one. And he didn’t want either one of us to go. We were going to go as a family, and we were going to stick together. My grandmother wanted us out of Germany in the worst way. She wrote, she had a brother in Holland. They would take us, but my grandfather said, no. If they are going anywhere, they’re going to go across the border, anywhere, but Holland is too close, they can invade Holland, they can invade any of those countries. And he was right, they did invade. My uncle, none of the family, most of my family in Holland didn’t make it either.9The family in Holland included Toni and Karl Hochstädter (Settchen Guckenheimer’s brother), their children Meta, Bertel and Helene, who was married to Max Kaufmann and had two children. With the exception of Meta and Bertel Hochstädter, they were all deported from Westerbork to Sobibor on July 20, 1943 and murdered.

And how did you get out of Germany?

With a Kindertransport I left, and there was a whole group of kids. I didn’t know anyone. My grandparents took me to the station. I don’t remember if my sister was alone or not, I somehow doubted. But my grandmother and grandfather, who they gave everything to us children, said goodbye to us. Did I cry? No. They didn’t want us to be upset.

Did you know what was going on?

I knew what was going on, but the last words were, „I will see you soon, we hope sooner than later.“ But they made it so sure that we would see you. They didn’t know if we would meet in America, or how we would… I didn’t know, but they assured me that we would be together. And really, I wasn’t sad when I left Frankfurt, you know, it was like an adventure. I was going to see them soon, and I had to be safe first.

Did you leave by yourself?

No, a whole bunch of children, but I didn’t know anyone. You know, at the museums, you see children transports, you see it on the screen, the trains, and you see the children coming out of the trains. I stand in front of it and I’m looking for myself, but I wasn’t filmed. But there were thousands of them, England took in 10,000 children.

So where did the train from Frankfurt take you?

Towards Holland, to the ship. It made stops in various towns, I don’t recall what they were. We stopped at the border town, I don’t know the name, to Holland. That’s when my uncle boarded the train, and he walked along until he found me. And we talked for a while. And then when we got to Hoek van Holland, which is not far, I mean, I don’t remember how long my uncle was with me on the train. We had to board the ship. And my uncle was religious, he put his hands on my head and said a prayer and they call it „Benchen“. You do that every time you leave on a train. Some people do it every Friday night. It’s the prayer you say to your children. It’s a wonderful thing. Every time we visited one grandparents, my grandparents Koch, my father’s parents, they did it a lot more than my grandparents Guckenheimer. My grandparents Guckenheimer were more modern, they went to synagogue on the high holidays. We children, we had to go every „Schabbes“. We also sang in the choir, my sister and I.

And your uncles name?

Karl Hofstädter.

Was he your father’s brother?

My grandmother’s brother, of my grandmother Guckenheimer.

And do you remember the prayer?

No, no. I think it is something similar that you say on Friday night, when the rabbi… or when the young couple gets married, I think it’s the same prayer.

And then you part ways with them?

Yes, but that’s when I woke up and realized, you know, it might be a long time before I would see any of them again. And I realized more, not so much even how long it would be, until I saw my family. It was more, I think in those days, when you’re 13, you’re more self-centered. I’m not saying selfish, but you’re thinking, „I’m on my own,“ which I didn’t realize until then. I was never away at camp. I didn’t have that in those days. I was with my family. And all of a sudden, when I got to Holland, that’s when I realized, hey, you’re on your own.

Was that when you passed on the umbrella?

Yes, to my uncle. And I remember my grandparents gave me an umbrella, and I was not to open it. It was a regular umbrella. I don’t think they had the little umbrellas in those days. And I should not open it. I realized that something was in that umbrella, and I gave it to my uncle. I said, „Oma wanted you to have this“. He took it and no word was said about it. I mean, I’ve been thinking about it. What could it have been? Maybe even my grandmother wrote, how terrible things are and who was beaten or what was going on. Maybe they didn’t know. Or something of value. I really, I don’t know. I know my grandparents would get Jewelry to Holland, because I got some of it back.

So then from Holland, how did you… ?

We got off at the ship. We got off in Hoek van Holland, bordered the ship and went to England. I don’t know which port it was. Maybe Sandwich. I don’t know.

How many children?

I don’t know how many was on that particular transport. I would say, my roughest thing would be maybe anywhere between 25 and 50.

So once you got to England, did you have any communication with the rest of the family?

When I got to England, I could communicate with my family. The main way to communicate was to write. I would write practically every day. It might have been a postcard or a letter, but I was always a good letter writer. And I had the two grandparents to write to.

So you so exchanged letters back and forth with both sets of grandparents?

Yes.

As well as your uncle and the rest of your family?

No, I did not communicate with my family in Holland, no. Because I know my grandmother is taking care of that. Children just write to their own.

And how long did their communication last?

Until the war broke out. The war broke out in September 3rd of ’39.

And didn’t your grandparents relay the conditions in which they lived in Germany? If they had to wear stars?

That was not until after I left, but the letters that they wrote are just heartbreaking. They wanted to get out. And in every letter it says, “Mrs. Adler, she left this week”, “Frieda and Julius Kahn”, they were good friends of them, “their son is in America. He’s sending an affidavit. They hope they can make it.” And we have pictures of them together yet, but they were lucky.

We just recently received all the letters that your sister got.

That’s right. You see, I could not correspond directly with my grandparents anymore as soon as war broke out. England and Germany was at war. But my sister, she corresponded back and forth.

Until the States were at war and it was all over.

Yes.

So going back to England, where did you first live once you got to England?

In Coventry, to a family, and I had everything with me. In Germany you gave a girl a trousseau, linens for when she gets married, so that she would have the things that she might need. I had it all. And Coventry was one of the worst bombed cities. The family I came to were good human beings. They had a store, clothing store, where they sold. In England you have places, stalls on market days, where you sell each day at a different little town. You sell your wares on the market. I went with them on the market days to all the little towns. And I was with them.

On some days that I had something to do, I stayed back at home. But I was on the go with them. And on the days that I stayed home, I was in the main store, which was in Coventry. It was a small store. It wasn’t open to the public, but where all their merchandise was kept. They had a little lady that did all the alterations from the people that bought if the coat needed shortening, or the sleeves needed shortening. And that little lady, she was crippled, the spinster, the nicest lady. I felt very comfortable with her and I stayed with her many, many days because I enjoyed sewing. This is where I learned how to sew.

She taught you?

Yeah.

Did you help her out with some of the…?

She gave me scissors to open things where I could see without making a hole in the garment. That’s how I learned how to sew. So they had people in a small town, and they rented a couple of bedrooms where we would go in the evening. It might be ten miles away from Coventry, because we knew Coventry was being bombed. And on the worst night that Coventry was hit the most, we were in a different town. But the house we lived in was completely destroyed. My things, everything was gone. And the family had to come back. They had nothing left in the house.

They shipped me, and I befriended a girl that lived across from me in Coventry. The two of us were shipped to Northern England to Harrogate, near Leeds, to a girl’s hostel where they took us in. We had a bed to sleep in. We got six pounds a week, which was nothing. You could buy a stamp, you could buy nothing. It might be fifty cents.

After a week of that, we took a bus to Leeds, and we went to a Jewish committee, and we said, „We have nothing. We need to go to work and we need a roof over our head. But we’d like to stay close together.“ My girlfriend, she came to a rabbi’s house to help in the household. I went just around the corner to a family Levi that had a little boy. He was three years old, and I became his nanny.

By that time, I was fifteen. I stayed there for about a year. You could work when you were sixteen. I looked for a room, found a room with a teacher that taught the ORT boys. The ORT boys were from Berlin.10“ORT” is an international Jewish foundation established in St. Petersburg in 1880. In 1937, the first ORT school was founded in Berlin with the aim of providing technical training for Jewish boys. Due to the massive National Socialist persecution, the school moved from Berlin to Leeds in 1939, along with its pupils and teachers (see ORT website). They came to Leeds, and that’s where I met quite a few every Sunday night at this Jewish club. And so I found a room there and I went to work.

Where did you work?

I don’t remember my first job… Oh, sure! I went to work in a munition factory. I took a man’s job. You worked eight hours a day. If you worked a woman’s job, you had to work twelve hours a day. That was three shifts. Every week, I had a different shift for eight hours. The machines were going twenty-four hours a day. We were turning shells for the war.

What kind of machine you work on?

A lathe. A huge lathe. I wore leather clothes because they had the hot from the iron, the char that fell off. You had to be sure that they didn’t fall into your gloves or else you’d get burned. It was a rough job, but it paid well, and I did that for quite a while.

And you meet different people with your background. Bon was a man. He had an agency and people that traveled for him and sold different merchandise. During the war, you didn’t have much to sell because very little was manufactured. But he had purses, leather, wallets, cigarette cases, writing materials. So I said, „Okay, fill a suitcase for me. I would like to do it.“ I took the train for a little town to the next little town, went to the stores by myself.

I was around eighteen. I asked for the buyer or the owner. Most of the time, those small stores don’t have a buyer. That’s the owner, and sold them for my samples. I took orders. And in the evening, I would sit down and write my orders, send them back to Leeds, and they would fill them. After it was delivered, I would get my commission. There was one time, most of these salesmen have cars, but, of course, to get gasoline, petrol, during the war was very hard. You were allowed very little, as a single young girl. But somehow there was always a way to get it.

There was one day, I rented a car for the day. I went to a driving school in Leeds, I learned how to drive.

Was this before or after you drove the car?

I learned before I went to the car. You had to be eighteen. I rented a car, and I was busy driving. I didn’t notice I went into a one-way street. The wrong way. And halfway down, a policeman stopped me. I had to stop, which I did. So he asked me, and he could see I was a greenhorn. He said, „What are you doing?“ I was telling him I was here for the day. I was trying to sell my wares. And he said, „Well, I can’t let you go on. Will you please back up, and we’ll call it a day. Don’t come down the street anymore.“

I did not get a ticket. So I looked at him and I said, „Officer, I didn’t get that far in driving school yet. How to back up? Will you please get in and drive the car backwards for me?“ And he did. He said, „Please leave this town and do not come back.“ But he just didn’t give me a ticket.

He just wanted you out. [Laughing] Talk about the social life in Leeds.

I was very independent when I was that age, which I’m not anymore.

Talk about the social life in Leeds.

Social life, you look forward from one Sunday night to the next. Then we had movie houses. I always had a date.

[Someone is calling from the background:] Omi was very popular.

I was young.

And pretty.

Sometimes you would go with another girl, which I did quite a bit, go to a tea dance on a Saturday afternoon. You have a tea, then you sit with your girlfriend, and single fellows that come around and just ask you for a dance.

So when did you meet the love of your life?

I don’t remember the exact date, but I was, I’m not sure if I was 16, I think. He was there with all the other fellows.

At one of the dances.

At all of the dances. They were there every Sunday.

And who took you home?

Usually in England, the one that you danced the last dance of the evening, it always finished around eleven o’clock, he’s the one that has to walk you home.

Tell the name of the dance of the last dance. „Who’s …“

The last dance was always, „Who’s taking you home tonight?“ It was a waltz. And so, if I wasn’t dancing with anyone else, he would ask.

Who is he?

Sigi, Sigi Veit.

How did your relationship start?

At the dance, we would say. Nothing, nothing, no love at first sight, nothing like that. He was just one of the boys. He was tall, but he was a good dancer, which I wasn’t really.

Big brother?

Yeah! He was in the same boat as I was, and I remember my sister or my aunt from New York would send me a food box. You couldn’t get a lot of things in England during the war, you had ration cards. And like little hot dogs in a can, that was a delicacy. When I got the package like that, I would invite him to come and share it with me. He was just a good friend.

Sometimes I was short of money, he lived from week to week. When I was short, I could always borrow from him. As a matter of fact, when I left from England to come to America we had a friendship. No romance, nothing whatsoever. And I borrowed fifteen pounds.

Sixty dollars?

I know it was sixty dollars in an in-exchange.

When did you come to the United States?

The end of October of ’47. Sigi, in the meantime, he was back in Germany with the American Army. Anyway, he always, whenever he came back home to Leeds, he would always stop by and say hello. We went to the movies once. We didn’t date. He took me to the movies once. In England, they have an intermission at the movies, and a lady comes around with a tray around her neck with Eldorado ice cream. And he said, „Would you like an ice cream?“ Of course I had to say no, because I didn’t have any money. Then he took me home again.

And the last evening in England, before I came to America, we went at the dance at the Jubilee Hall. On the way home, I lost my watch. When I came home, the first thing I’d always do is run to the bathroom. At the bathroom I realized I lost my watch. I ran out the door and I called Sigi, „Please come back.“ He was already walking to his home in England. I said, „Please help me look, I lost my watch.“ So we went, it was in fall. The streets were full of leaves, and sure enough, we retraced it and I found my watch. These were the excitements.

And then when you came to the United States, where did you live?

I came to my „Mischpoke“ in New York. I had my family in Forest Hills.11This refers to Aunt Laura Liebmann, the sister of her grandfather Ludwig Koch, who emigrated to New York in 1938. I stayed one week and another, and in Washington Heights. Sigi happened to leave at the same time as I did. That was coincidental. He went by boat and I went by plane.

I let my affidavit expire a couple of times. I didn’t want to come to America. I loved England. But when I heard that my grandmother, my father’s mother, had made it through a concentration camp and she was shipped to America, I knew she needed help. She was way in her 60s. She came to Chicago, where my sister lived, so I knew I had to be bound for Chicago.

When Sigi came back from working for the American censorship division, he said he’s going to America. It was the same time as when I was going. I borrowed 60 dollars from him. I needed to ship whatever clothes I had. In New York, my uncle, it wasn’t a first uncle because my father and my mother were only children, it was a second uncle.12This refers to Uncle Erich Liebmann, the cousin of her father Otto Koch. He gave me 50 dollars to get started in Chicago. And out of the 50 dollars I gave Sigi 10 dollars. Little did I know then that I would marry him. But the 50 dollars I still owe it.

Talk about your marriage. When did you guys get married?

We came to America the end of October. Sigi said he’s going to start finding work in New York. I said I was going to Chicago. He said, „Maybe I’d like to come to Chicago over Hanukkah 1947-48 to meet your sister and your grandmother.“ And sure enough, he came and by train and I met him. The name of a train, I don’t remember it….

“Pacemaker”?

The “Pacemaker”. And my grandmother had knitted me a brown babushka. And I wore that because it was winter time in Chicago and on the platform she thought I’d be cool. I wore that babushka. He got off the train on the 63rd street and when he saw me with that babushka he wanted to get back on the train. I didn’t look attractive at all.

Anyhow, he got to meet my sister and grandmother. He was figured he’ll be gone after Hanukkah. I had a date for New Year’s Eve from a young man that knew my family from back home. And he was established. He was eleven years older than me, but his mother and my grandparents were good friends. So he wanted to take me out New Year’s Eve and he made the date a few weeks in advance.

I didn’t know is Sigi going to go back to New York. I mean it would be over a week that he would be here. What’s he doing here so long? But he didn’t say one word. I was working at the fair store, I showed him Chicago and he met my family so I thought he would go back. Well, but he didn’t make a move.

And my sister, she lived in an apartment building, there were lots of people there. They get together every New Year’s Eve. They didn’t go out. She said, „We’re getting together there. If you’re here, you can come to the party.“

And Sigi says, „Okay, we’ll come to the party.“ So I had to cancel my date. And New Year’s Eve he proposed and said, „Two can live as cheap as one. Please marry me.“ That was New Year’s Eve from ’47 to ’48.

He went back to New York. I said, „You find an apartment and we’ll get married and you make arrangements and I’ll be back as soon as you can.“

Well. In those days, you had to pay under your nose to get an apartment. My sister had a friend in the real estate business and she got us a furnished apartment on 47 Drexel Avenue for February 1st. Okay. It was 54, 50 for the rent. I wrote to Sigi, „What should I do? Take the apartment?“

The first of February happened to be a Sunday. Sunday afternoon a cousin of my father’s best friend was a rabbi in Chicago on the north side. And my father’s cousin, Erich Liebmann, said, „I could call him, he would come out and marry us.“ He came to the place. My grandmother went to live with a German family. And the rabbi came to her house. He knew my grandmother from back home. He put Sigi’s head in woolen talas from back home. He put the talas over both of our heads.

That was our „Chuppah“.13The Hebrew word „Chuppah“ refers to the canopy at a Jewish wedding ceremony. We were all of eight people. He mumbled a few words, but they kept us going. It’s 63.5 years, and it’s the best thing that happened in my life.

So tell me what two young kids from Germany, coming to America, tell me about the family that those two people created.

The family we created, we didn’t think about creating a family. We got married, and we had to both work to get going.

Did you husband have a job?

My husband didn’t have a job. I had a job at the fair store. But whatever I made I spent because I had no clothes in America. They wore different clothes that they did in England. The skirts were really short and here it was out of style.

We got married 1st of February, ’48. I wanted for the first time to buy him a chair that he could call his own. We lived in a furnished one room with a Pullman kitchen, you know, that you open up an inner door bed that you bring out of the wall at night. We had an own bathroom. But we had no big closets or clothes. We didn’t have clothes to hang up in. So whatever we had, first we bought a buffet that we could put a few things there.

Then we’d got an apartment that had still an inner door bed, but we had a proper kitchen with a dinette next to it where we could eat. That was the same, we had one room. But we had a separate dinette and kitchen.

We lived there two years until we could afford an unfurnished apartment because we had to buy furniture. We did that. We decorated that apartment. We painted ourselves. I made the curtains. Whatever we had, we put in the apartment. Some was second-hand. We made do.

And then thinking about a family. Barry came along after three and a half years. He was our oldest. And we had him in that apartment. He didn’t have a bedroom of his own. The crib was in our bedroom.

Sigi went to work. I had to quit working. But I still worked a little bit. I made eleven dollars and a quarter. I was babysitting. We had a young girl that went to school nearby and her mother was working. After school, she would come to me for three hours in the afternoon. And I made eleven dollars and a quarter per week.

That girl’s mother, the family had a store, confectioner’s, sometimes I could work a day there. Whenever I could work and Sigi was home to take care of our son, I would work. He worked full-time, of course.

Three years later, we had a daughter, Debbie. By this time we’d already saved enough as a down payment for a house. We are both frugal. We saved. We saved and we did little by little. I never thought I’d have a house.

Did you ever in your wildest dreams think your family would grow so big?

In those days, having a baby, all you thought about is a baby. You never gave it a thought that this child would grow up, that he would need shoes. You never thought that he would grow up.

And here you are with six grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

That’s right. I’m the richest lady there is.

Tell us about your wonderful life now.

My life is my family. First is my husband. Our children. Barry married a very nice girl, Julie. We were very good friends with her family. They have two boys, Aron, named after my deceased father-in-law. The second one is named after his maternal grandfather.

Our daughter, Debbie, married a very nice young man. His mother came from Frankfurt, his father from Vienna. Their daughter, the oldest daughter, Rachel, has a young baby, Dylan, who is the light of our life right now. The second one, Becky, is married. And the third one, Emily, is engaged to be married. And Matthew, the youngest, he is fancy free.

My life is good!

Anmerkungen / Notes

- 1All images on this interview page are from Ruths‘ photo album.

- 2This happened on the night of March 31 to April 1, 1933, when the National Socialists attacked Jewish stores across the country and called for a boycott. SA members were also posted in front of the shops to record and intimidate all customers.

- 3This is the “Dr. Heinemann’sche Mädchenpensionat”, a private Jewish school at Mendelssohnstr. 84 in Frankfurt’s Westend district.

- 4“Schabbes” is the Yiddish word for Sabbath.

- 5This refers to Rosa Guckenheimer, the wife of Adolf Guckenheimer’s brother Ludwig Guckenheimer, who died in San Remo in 1937.

Rosa and Ludwig Guckenheimer, ca. 1936 - 6This refers to Uncle Emil Liebmann, the husband of grandfather Ludwig Koch’s sister Laura.

- 7„Shiva” means „seven“ in Hebrew and stands for the time of mourning in the first week immediately after the funeral of a close family member.

- 8„Affidavit“ is a notarized declaration of surety that enabled persecuted persons to enter the USA.

- 9The family in Holland included Toni and Karl Hochstädter (Settchen Guckenheimer’s brother), their children Meta, Bertel and Helene, who was married to Max Kaufmann and had two children. With the exception of Meta and Bertel Hochstädter, they were all deported from Westerbork to Sobibor on July 20, 1943 and murdered.

- 10“ORT” is an international Jewish foundation established in St. Petersburg in 1880. In 1937, the first ORT school was founded in Berlin with the aim of providing technical training for Jewish boys. Due to the massive National Socialist persecution, the school moved from Berlin to Leeds in 1939, along with its pupils and teachers (see ORT website).

- 11This refers to Aunt Laura Liebmann, the sister of her grandfather Ludwig Koch, who emigrated to New York in 1938.

- 12This refers to Uncle Erich Liebmann, the cousin of her father Otto Koch.

- 13The Hebrew word „Chuppah“ refers to the canopy at a Jewish wedding ceremony.