(Letzte Bearbeitung / last updated on 05/02/2025)

At the time of this interview, Lila Williamson, née Lieselotte Koch, was 88 years old. The original video can be found here and was provided to me as a copy by her children Leslie and Lance when I visited them in Chicago in October 2024. I have slightly improved the interview transcript from the Holocaust Museum Florida, annotated it and added some pictures.

My name is Marina Berkovich. Today is August 22, 2012. I am conducting an interview with Lila Williamson, who is a Holocaust survivor. This interview is conducted on behalf of the Holocaust Museum and Education Center of Southwest Florida for the Oral/Visual History Project. The purpose of this interview is to preserve testimonies of individuals in Southwest Florida who personally experienced and observed the evils of the Holocaust so that future generations will know what happened.

What is your name?

Well, my name is Lila Williamson today. I was really born with Lieselotte Koch. That’s my birth name.

When were you born?

October 1923 in Mainz, Germany.

What was the exact date of your birth?

October 2.

And how long did you live there?

I never lived there. My parents lived in Alzey, which wasn’t far away. But the hospital obviously wasn’t good enough for my father, so they went to Mainz for the hospital. But my parents and my grandparents lived in Alzey.

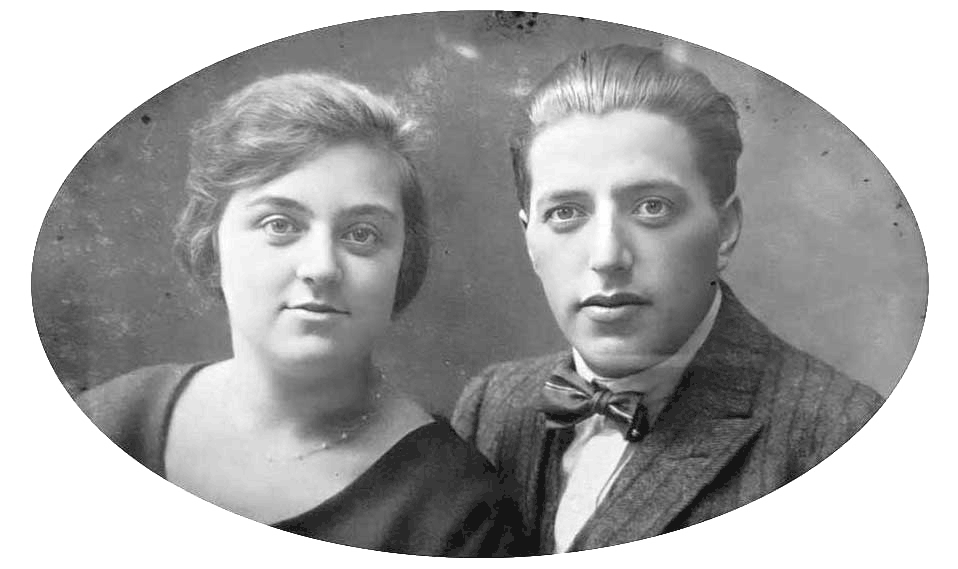

What was your mother’s maiden name?

Guckenheimer, G-U-C-K-E-N-H-E-I-M-E-R.

What was her first name?

Erna, E-R-N-A.

Where was she born?

In May 1902.

And what country was she born in?

Germany.

Tell me a little bit about your mother.

I have absolutely very little recollection. She died when I was five years old.

What was your father’s name?

My father’s name is Otto, O-T-T-O.

Where was he born?

In Alzey.

Do you know the year when he was born?

1898. I don’t remember his birthday.

Do you know what his occupation was?

He was a salesman. He was really in business with my grandfather. They had a mill where people brought their raw corn and wheat, and they would mill it and make it into flour. And I saw people come and carry out the sacks of flour.

Did you have or do you have any other siblings?

I have a sister. My sister Ruth is a year and a half younger than I am, and she lives in Chicago.

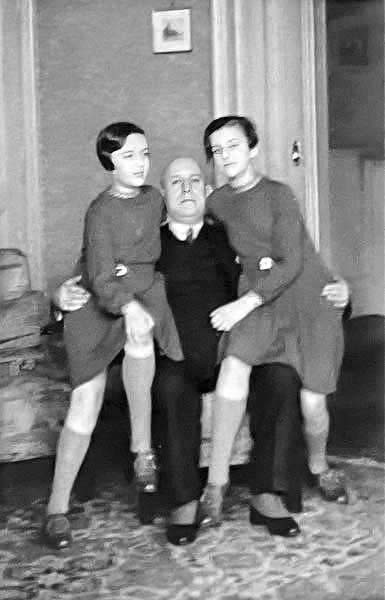

What were your father’s parents’ names? Where did they live? What did they do?

My Oma was Thekla, T-H-E-K-L-A. And her maiden name was Engel, E-N-G-E-L. And my grandfather was Ludwig, L-U-D-W-I-G.

And what were their last names?

Koch.

Where did they live before the Second World War?

In Alzey. They had a big house with a yard, and beyond that was their business, the mill. And beyond that was a garden with vegetables and trees.

What do you remember about them?

Very little, because once my mother died, my sister and I went to live with the other grandparents, with my mother’s parents, who lived in Gross-Gerau, and they figured they could take better care of us. But we visited the Koch grandparents. We were sort of shuffled back and forth. But mostly I lived in Gross-Gerau, and I went to school there. I started grammar school there. And grammar school lasted until about second or third grade. And by that time, the next thing I really remember is Kristallnacht.

What were the names of your mother’s parents?

The names of my mother’s parents? Guckenheimer.

What was your grandmother’s name?

Settchen, S-E-T-T-C-H-E-N. And my grandfather was Adolf, A-D-O-L-F.

What did your grandfather do?

Well, he had a lumberyard. Big lumberyard. He sold lumber and he sold coal and he sold most anything that went with building. This is where we lived [shows 3 photos]. This is the house we lived in:

And this was part of the lumberyard:

And this was sort of living room, and this was bedroom [points to windows on the second floor]:

It’s a very nice house. So what was your grandparent’s social position in this town?

Oh, they did everything. They belonged to Temple. We had a Temple. And that’s where we went for holidays. And they went Saturday mornings. That was a ritual, and that’s where they went. With the neighbors that lived around them, not all were Jewish. Some of them were Jewish.

At that time, did your grandmother work as well?

No.

Did your mother work?

No.

What was your mother’s occupation that you told me?

None. I guess she was a housewife and a mother.

Do you remember what she looked like?

Really not. Very little. No. My grandparents, the ones in Gross-Gerau, we had help in the house, and my grandfather even had a car. We had a man that would drive us. And sometimes he would drive me to school.

Did they have any other kind of help, domestic help? Did they have a cook?

Yeah, they had a cook. And she would come in the morning and stay and do whatever. She did a lot of the cooking. My grandmother did a lot of the cooking.

The help that was working on your grandparent’s home, were they Jewish?

No! Not at all. They lived in the next town over. I don’t remember how they came. But I saw her – what was her name? Gretchen! I saw her when I went back to Germany in 1991 or 92. I went to see her.

Who else worked at the home? You and your sister were very young, did you have anybody who was taking care of you other than your grandparents?

Yeah, we had a Kinderfräulein, because my grandparents felt they were too old to put up with us kids. We had very nice Kinderfräuleins. I also met them later on. And they weren’t much older than we were. But they were nice Jewish girls from good homes who taught us manners.

You were about how old when they taught you manners? This was before you started school or after?

No. They were there. When I went to school they helped with schoolwork. They did lots of things. They were my grandmother’s right hand.

How long did you live in Gross-Gerau?

Till after Kristallnacht.1The event to which Lila refers and which forced the grandparents to leave Gross-Gerau was not Kristallnacht, but the so-called “boycott of Jews”, which was initiated by the SA throughout Germany on the night of March 31 to April 1 with attacks on Jewish businesses. As Lila will later explain in the interview, the Guckenheimer grandparents were so severely affected by this that they felt compelled to give up their family business and move to Frankfurt, where they hoped for more security in the anonymity of the big city and in the environment of a strong Jewish community. The move from Gross-Gerau to Frankfurt took place in September 1933.

What language were you speaking at home?

German.

Did you speak any other languages at all?

No, no.

Were your grandparents, when they went to the synagogue, were they bringing you up to have religious beliefs?

Yes, definitely.

How were they raising you? Were they giving you lessons? Were they taking you to the Temple for lessons?

Part of it was the Temple program. And we were part of it. My grandfather was a „Macher“.2In German, the term “Macher” is used to describe a leader with assertiveness who takes action and puts his plans into practice.

So where was your school located?

Five, six blocks away from where we lived.

Was that a Jewish school or a secular school?

No. Public, local school.

Can you describe anything about your school? What do you remember about your early education?

I would say today it was plain basic school. We learned to read. We learned to write. We learned to play. And it was very open. The windows were always opened for fresh air. And there weren’t many kids in my class. It was plain basic grammar school.

What else do you remember about Gross-Gerau?

Gross-Gerau was a lovely town. They grew asparagus in the fields, and especially white asparagus. That was their specialty, and they had warehouses and canneries, and that was a big to-do. What else do I remember? We had lots of forests around us. And we would go there and walk and pick mushrooms.

Who were your playmates? Do you remember anybody?

I really didn’t have any playmates then. We were kept pretty well close to home. The kids across the way, they were our age, was a doctor’s kids and actually was a doctor’s grandchildren. We sometimes played ball with them. No big deal.

Did your grandparents have a lot of friends?

Yeah, they had a lot of friends from Temple and I remember having Passover dinner with this set of friends and that set of friends, and they all went to Frankfurt to the big hotel where they had Seder for the people who wanted to come.

Very sad note: one year – I don’t know how old I was, five, six, seven. Mrs. Gottschalk died just before Seder, and it sort of put a damper on it. But Seder went on and we ate. That night we went back to Gross-Gerau.

How old do think you were at that time?

Six, seven, thereabouts.

How old were you when you left Gross-Gerau?

When I left Gross-Gerau, I went into third grade in Frankfurt. Was I eight, nine, ten?

What happened? Why did you leave Gross-Gerau?

It was Kristallnacht.3On the night of November 9-10, 1938, the so-called “Kristallnacht”, Lila’s father Otto and grandfather Ludwig Koch were arrested in Alzey. More than 30,000 Jewish men in Germany were deported to the Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. At this time, Lila’s grandparents Guckenheimer had already left Gross-Gerau and been living in Frankfurt for over 5 years. The event to which Lila refers here and which had prompted her grandparents to move to Frankfurt was not “Kristallnacht”, but the National Socialist call to boycott Jewish stores, which was initiated by National Socialist henchmen throughout Germany in the night from March 31 to April 1 with attacks on Jewish stores.The Nazis threw bricks into the bedroom windows and one of them hit my grandmother in the head. She told us to go to the bathroom where it was walled in, but they hit the bricks there too. Somehow, this is really vague. I don’t know how we got from Gross-Gerau to Frankfurt, where there was an apartment. We then lived in an apartment and I went to school there.

What else do you remember about that day? How long did it last?

It was an all-night affair. Some of the people that threw the bricks, we found out years later from the doctor, the grandpa doctor, of who they were. They were people that used to be my grandfather’s customers.

They were German, obviously.

German, yes.

When grandmother was hit in the head, what happened?

Somehow, the doctor came over. That was much later, during the night. We waited until the bricks sort of stopped. We just sat there, and the doctor came over and bandaged my grandmother. But no hospital – nothing like that.

Why not?

I don’t know.

What else do you remember after you waited all this time and the doctor came? Were you scared?

Sure, sure we were scared, because downstairs lived my grandfather’s brother and his wife.4This refers to Adolf Guckenheimer’s brother Ludwig, his wife Rosa and their two daughters Else and Luzie, who lived on the first floor of the Guckenheimer brothers‘ house. Both brothers sold their business and their house after the attacks. Adolf and his wife moved to Frankfurt with their granddaughters in the fall of 1933, while Ludwig decided to move to Wiesbaden with his family. They weren’t hurt, hit, or anything. They just threw the bricks through the second floor. Above us lived our handyman, who was the chauffeur and who knows what else he did. We never saw him that whole night, so I don’t know whether he was in cahoots with these Nazis or not. We don’t know. I don’t know.

How did you know that they were Nazis?

I presumed the doctor across the street told us later. Now, I don’t know how much affiliated he was. I presume some, because his patients were locals.

And what happened after the Kristallnacht?

I don’t really know what happened from that night till we got to Frankfurt. But all of a sudden, I remember I lived in an apartment with our furnishings. Gretchen, our maid, and her husband were very busy getting us settled in Frankfurt. The furniture came there. Many years later, when I went to see Gretchen, where she lived, I saw some of the furniture that belonged to my grandparents.

Did she move to Frankfurt with you?

No, she lived in this little town in between. [Mörfelden?] How she commuted, I don’t know. There was a train and there was a bus, and she came. And I remember for her to come to Frankfurt, she would always have something in her bag, whether it was a chicken or eggs or cabbage or whatever she brought that day.

What do you remember about the Frankfurt apartment and your life in Frankfurt in general? What kind of a neighborhood were you living in?

Very fancy, very nice. We lived on Hammanstraße right next to a park.5In September 1936, Adolf and Settchen Guckenheimer moved into a rented apartment at Hammanstraße 4, about one kilometer from the Philanthropin. At the time, Hammanstraße was mainly inhabited by well-to-do Jews. It bordered a small municipal park, which was then called Eysseneckpark and was renamed Holzhausenpark after the war. Prior to this, after moving from Gross-Gerau, the Guckenheimer family lived in a rented apartment in Scheffelstrasse, which was in the immediate vicinity of the Philanthropin. It was quite a ways to walk to school. I went to the Philanthropin, which is a Jewish parochial school, and my teacher was Rabbi Neuhauser – with a stick.

What do you mean?

He always had a stick, and if you didn’t do something right, he’d hit your fingers. [Laughs]

What did he teach?

Mostly Hebrew, mostly History. We had other teachers for English and we had another one for math. I don’t remember the art teacher, but this was a very high-class school, private.

Did your sister also go to this school?

No. The curriculum was quite stiff and she wasn’t up to it. She went to a nice little girls’ school.6Lila’s sister Ruth also attended the Philanthropin from September 1933 to spring 1936. There is a class photo with her from 1936. She then transferred to Dr. Heinemann’sche Mädchenpensionat in Frankfurt’s Westend in Mendelsonstraße, where her mother and grandmother Settchen had also previously been school girls (see interview with Ruth Veit, née Koch).

Can you tell me about what a regular day was? You’d go to school, what happened after you came out of school?

I walked to school with some of my Jewish friends that also went to that school. Some of them still live in and around New York. When I was there in the year 1999, I saw them. I saw six of them. They’re all there yet. School was school, and we went there mornings. We came home for lunch. We had whatever, and we went back. The afternoons were mostly spent with the Kinderfräulein taking us to the park, either walking with a ball or a bicycle. But it was what I thought of that time pretty regular. That’s what kids do when they go to school.

Do you remember what kind of games you played at all?

Most of the games we played were played in the schoolyard – big yard. There was sort of a volleyball kind of game. The girls and the boys were separated. And of course, we always looked at the boys. We had a gym, in the gymnasium inside, but we also had what they call today field and track games running. Sports were emphasized.

After you moved to Frankfurt, what was your grandfather doing?

Nothing. I presume he played the stock market.7From 1933 to 1935, Adolf Guckenheimer ran a small coal business in Frankfurt at Keplerstraße 7a until the Jewish population was banned from all participation in economic life.

What happened to his lumberyard?

I have no idea.

And your grandmother was she at home cooking?

Yeah, that was her job. But they didn’t do much more. They still traveled. Their favorite place was the Black Forest. I know I went with them once, and we went to Switzerland and we went to Holland. Even then.

What year was that?

1933 and ‘34. Kristallnacht was 1933.

Did your father come to visit you in Frankfurt?

No, no. These grandparents did not talk to these grandparents. They just didn’t talk. They just had us as common denominator. And came to our school vacations, we would go see the other grandparents in Alzey. They still lived there, not in the big house anymore. That whole thing, that whole mill – “Mühle” – was taken over by somebody. I don’t know if they were Nazis. They were non-Jewish people, and they ran it because the town depended on it, and especially the Catholic Church. The Catholic Church was supplied by some of the flour that my grandmother sent to them. They kept that up because I knew that when I went back and I went to the Catholic Church and visited one of the nuns that used to take care of my grandmother. She came once. My grandmother had leg problems, and this nun came and would bandage my grandmother’s legs, but she always went home with a little sack of flour. Yeah.

Going back to your life in Frankfurt and as you were in the school and the times started to change, did you notice how the times started to change?

Yes. They started to change, but I lived very sheltered between my grandparents and the Kinderfräulein and the schoolmaster, the people in school. We saw very little. There were many things we didn’t do anymore. I used to go to a dancing class that a non-Jewish lady conducted. All of a sudden we didn’t go anymore. She didn’t want us as students, she didn’t want us to come to her studio, she wasn’t willing to teach Jewish children.

Did she tell it to you directly?

No. I don’t know. I presume my grandmother told me, “You don’t have dancing lessons anymore.” I don’t think they really discussed why or why not. But today I know. Years later I knew.

What else was changing?

That was one of the things. On Saturday afternoon we went to a restaurant. It was the thing to do. You went there and you had “Kaffee und Kuchen”. Our friends were around there and their children. All of a sudden we didn’t go there anymore because somebody was there that didn’t want us to go there. I don’t know some of the reasons – I really don’t. These are things that were kept from us children. You didn’t talk to your kids, you didn’t tell your kids everything. What the kids shouldn’t know, they didn’t discuss. I didn’t know what money was until I was nearly ten years old.

Why not?

I didn’t need any. Somebody else handled money for me. All of a sudden I grew up and I had to know.

Whenever you had money, what did you use to buy with money?

Who knows? Kids’ stuff, pencils. I remember buying pencils, yeah.

How long did you stay in school?

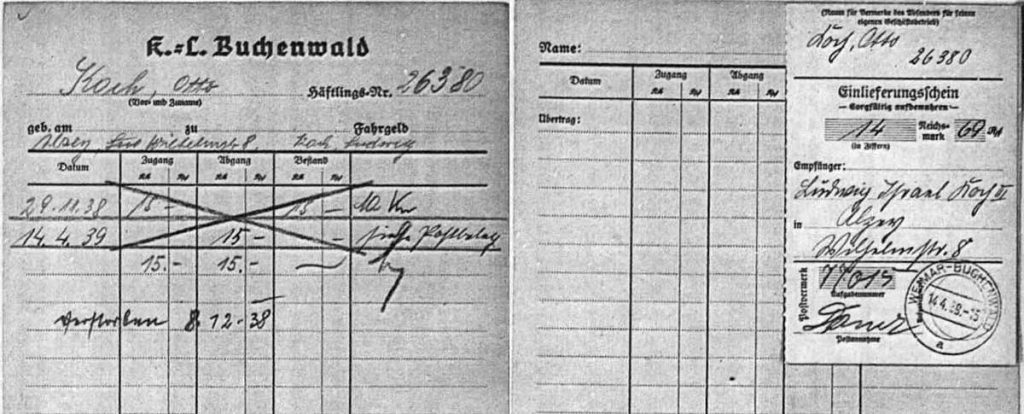

How long did I stay in school? Until 1939 or 40. Until it became obvious. Oh, by that time in 1939 my father still lived in Alzey, and he was one of the very first people to be picked up by the Nazis for the concentration camp.8Otto Koch was arrested during „Kristallnacht“ on 9.11.1938 and deported to Buchenwald. He died there on December 2, 1938. His ashes were sent to his parents in Alzey. Lieselotte’s sister Ruth describes many of the details of her father’s arrest in her interview from 2011.

This was in what year?

1939.

Do you know which concentration camp?

No. No.

What is his fate? What happened to him? Did he die there?

Four weeks later we got a notice that they’re sending the ashes home. No comment. Not how, why, when. He died and they were sending the ashes home.

Did you ever talk to his parents about it?

Sure, we went there. There were funeral services for him. Ashes. There was a family plot on my grandfather’s side where some of the Koch people were buried and that’s where they made room for his ashes.

He was about how old at that time?

He was just over forty. 1898 – so 1939.

Did you understand at that point in time what a concentration camp was?

No, absolutely not.

Did anybody from your family understand?

No, no. It was talked about very thinly in school. None of the other kids’ parents had gone. Frankfurt was a big town, and I didn’t hear who went. A lot of the kids at school immigrated at that time with their parents around 1938 and 39.

And where they immigrate to?

Who knows. Some went to South America. Some of them went to Canada, and a lot of them went to New York.

When you were at school at that time and people were emigrating, were there any people that didn’t come to school? They were just disappearing and nobody knew what was happening to them?

Yeah. They just disappeared. They were gone.

And did anybody talk to the children about that?

Kids were gone with their parents.

But in school, did anybody talk to the children about it?

I don’t really know.

So how were you explaining that at that point in time?

At home they were talking about it, that we couldn’t stay there much longer and that we ought to go maybe to Holland where we had other relatives. The Jewish organizations in Frankfurt were busy saving the children. My sister, who was under a certain age – I don’t know, was it under thirteen – she could be adopted by a family in England. So off she went to Coventry. And I was with a group called HIAS and they were the ones who organized the Kindertransports. Somehow I got onto that and went to England.

Was it the Women’s group in these organizations? How did you learn about this Kindertransport?

It’s a local group that my grandfather I’m sure supported.

Were your grandparents looking for a way to place you?

Yes. They had to find safe places for us.

Why didn’t they go?

My grandfather couldn’t leave his money. That was a big thing at home. My grandmother wanted to go and go to Holland and he said, “No, we’ve got it good here. We stay here.” That I remember.

And by that time – other than the events of the Kristallnacht – was he mistreated in any way or did he believe that Germany was all beautiful?

Yeah, that Hitler will go away! He came, he did his thing, and he’ll go away. I’ll be safe here with my money. That was his philosophy. There was a lot more to it, but that was it. Yeah.

So they were discussing the safe ways for children to be sent away on their own, on your own?

Yes.

They were discussing it in front of you?

Yes. My father was gone and dead already when they sent us. Can you stop a minute? [Short break]

One of the trips, one of the vacation trips, I was sent on to Holland. My mother and my other cousins are a generation off, because we were much younger. So I was close to the cousin in Holland. And I visited her later on when she lived in Switzerland.9The person in mention is Meta Hochstädter (1903-1985), the daughter of Lila’s great-uncle Karl Hochstädter (1876-1943), who is the brother of Settchen Guckenheimer. And that’s when she told me that my grandmother had made a dress for me and sewed some of her jewelry in there. And that’s how I went to Holland. My cousin in Holland then promptly took the dress apart and found the jewelry. Here’s one piece (shows jewelry), but that’s all. But that’s what they did. Very material-minded.

So, as they were planning for you to leave, were your servants still working for your family?

By that time they had left. They just came when nobody was looking. And again, Gretchen would bring something, something to eat.

Were you not getting enough food to eat at that time?

I don’t know. All I can tell you is that we always ate good.

So do you remember how you were getting ready for your trip abroad?

My grandmother packed a little suitcase for me, and I don’t remember really what was in it. But when I got to England, I got packages from her with clothes and especially underwear. I should never do with dirty underwear. So I had clean underwear. And those packages came and they sent little goodies. Things she baked. And she still wrote to me in 19, what was it, ’39 and ’40.

Do you remember what date you left Germany?

Really not.

Do you remember how you left Germany?

I said goodbye to my grandparents and some lady came and took me to the train. Then eventually – I don’t really remember of how I got to England But in a transport, part of it was by bus. Yeah.

Do you remember how you were dressed? What season of the year it was?

No. Clothes, a skirt and a blouse, that was the uniform. Yeah.

Did you know what you would be doing in England?

Yes, I was supposed to live with a family that had a son about my age, and we were supposed to go to their Temple school together. When I got there, the mother of this boy looked at me and she said, “You two can’t live in the same house.” That was too tempting. By that time we were sixteen. So they shoved me off to their son who had a wife and a baby – not too far away. I learned to do things I never knew they existed. I learned how to lay a fire. I learned how to eat smelly fish [laughs] – some of these things. Take care of this little boy. Not exactly physically, but to watch him, and to push him in some kind of a carriage. But in the morning, I had to get up and lay the fire and make the coffee. I never knew how to do that!

When you arrived to England, were you alone or did you arrive there with other children as well?

I went to Temple school for a while, but they decided that wasn’t for me. They needed me to take care of their child, so that was the end of my school. And that family lasted just so long. They were ultra-orthodox people. You know, we went to Temple the whole bit.

Do you remember their name?

Their name was Adler, A-D-L-E-R. And I don’t even remember the child’s name. They were lovely people, but I didn’t suit them. So then I was shoved off to another family who had teenage girls. They were 11 and 12, and I could learn English from them. They went to public school. They were not ultra-orthodox. They were – they weren’t reformed, no – conservative. Temple still on Saturday morning. Of course we walked to Temple, you know, because you didn’t drive. I stayed with them until somehow this HIAS organization who is nationwide, international, found my cousin, aunt, whatever you want to call her. She’s a distant cousin to my grandmother Guckenheimer, whose maiden name was Hochstädter. Herr name was Hochstädter too. She was here and she wrote out this affidavit for me. I presumed that in years gone by, my grandfather had the insight to spread his money a little here and a little there. I know there was some in Switzerland. But she had some money to take care of me and my sister or whatever. But I should never be a burden to her.

When you were in England, do you remember the name of the town that you lived in?

Manchester. Manchester was a working town – dirty, coal mining, coal shipping. They were on water and there was lots of trade with the boats, with the coal being shipped. Mr. Adler was a lawyer. But the second family, I don’t even remember their name. They were horrible! He was just a salesman. I would say he made enough money to feed his family.

Did you know anything about the War at that point in time?

Of course we did. We knew what air raids, bombs, shelters are. When you heard the sirens, you hid in the shelters, either in your house or something close by. We happened to have a school close by where we ran to when we heard the sirens.

How often was that happening?

It happened. I don’t know. But in the meantime, my sister lived in Coventry and Coventry was one of those towns that were completely bombed. And the family she lived with, they lost their house with rubble and bombs. She learned to shift for herself. The family went, I don’t know where the family went. But they didn’t take care of her either. She went to live in Leeds. She left Coventry and went to live in Leeds.

Were you in touch with her at that time?

Yes, somehow. We knew where we were. No intimate phone calls or postcards. But we knew it.

Were the people from HIAS or any other Jewish organizations helping you, coming to check on you or facilitating your communication with your sister somehow?

I don’t know if HIAS was involved; I don’t know. It was a miserable, miserable year in England. In 1941, I came here. That was through HIAS. They took the children that had affidavits in America and put them on a boat. The boat was a minesweeper. It took about ten days. There were six girls to a cabin. One of us was more sick than the next one because seas were rough. You had to dodge mines in the sea, but somehow we made it. We were taken care of. Not grand, but somehow we made it.

At that point in time, did you let your grandparents in Germany – did they know that you were going on to United States? Were they still in communication with you?

No, no. I lost communications with them early part of 1940 when the Guckenheimers went to one concentration camp and the Kochs went to another, and that was the end.10For Lila, the trauma of being a Holocaust survivor apparently blocked her memory of the end of her relationship with her grandparents for decades. Between 1940 and 1941, both the Guckenheimer grandparents and the Koch grandparents wrote her dozens of letters. For the Guckenheimr grandparents, the correspondence ended shortly before their deportation in November 1941. For the Koch grandparents, the correspondence ended at the same time when the USA entered the war. Many of the heartbreaking letters that Lila received have been preserved and can be read on this website.

Did you know that they were going to a concentration camp?

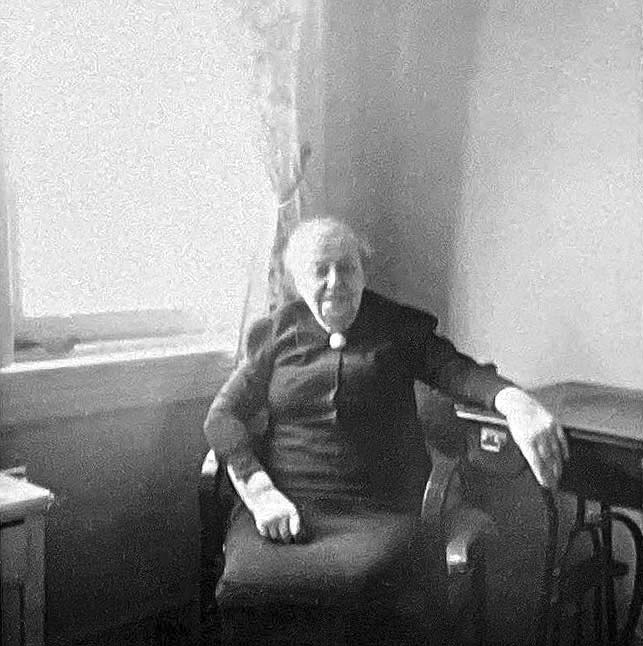

I presume through HIAS, I was told. Now, the Kochs, whatever happened to them, they stayed alive. Whatever my grandmother did, she did sewing for the Nazis, because that grandmother I brought here, and that’s how it came out. But my grandmother Koch was always the sickly one. She was the one who the nuns took care of for her legs. But she lived, and somehow they made it. My grandfather died as she would put it, “old age”. He was weak. He couldn’t handle some of the food and some of the doctors, whatever was available. But my grandfather had a sister in New York, and she helped my grandmother from there to New York, promising that I would get her.11The person in mention is Aunt Laura Liebmann, née Koch, Thekla’s sister-in-law, who emigrated to New York in 1938. This was strictly a stepping stone so that she could somehow recuperate, rest a little before she had to put it on me. After all, I was her granddaughter.

So in 1941, when you left England, do you remember the date that you left England?

Yes, sometime in April.

Do you remember the date that you arrived to the United States?

I got here.

Do you know what time of the day was it? Did you see the Statue of Liberty when you came on the minesweeper boat?

Of course I saw the Statue of Liberty!

Did you know about the Statue of Liberty?

Yes, yes. We were told on the ship to be sure to be on deck to see the Statue of Liberty. We were there, as sick as we were, but we were there! [Laughs]

And we waved to her, yeah. Another cousin on the Guckenheimer side, they immigrated, they were the daughters of the people on the first floor in Gross-Gerau. They immigrated something, I would say, 1937-8. They went to Italy early, early, early in the 1930s. They ran a hotel. Us kids, we would go there for vacations. But they came early and they went to New York. And she’s the one who met me at the ship, the boat.12The person in mention is Luzie Levi, née Guckenheimer (1906-1962). She is the daughter of Lila’s great-uncle Ludwig Guckenheimer (1873-1937), the brother of Adolf Guckenheimer. Lila lived with Luzi’s family in the Guckenheimer family home in Groß-Gerau until 1933. In 1937, Luzi and her father fled to San Remo in Italy. They apparently tried to run a hotel there. But Ludwig Guckenheimer died in San Remo on 27.6.1937. Luzie escaped with her husband Julius Levi from Italy to New York.

And do you remember your sentiment as you stepped onto the American soil?

I was so sick. The first thing she did was get me a bottle of seltzer water, as we called it “Bitzelwasser”. And she said, “You drink this and it will settle your stomach.”

And how long did you – ?

I stayed with her probably a couple of weeks. Her daughter my age, you know, we were there. And eventually I took a train to Chicago.

Stay in New York for a little bit. What do you remember about New York when you arrived?

First of all, I slept. And then there were quite a few cousins I never knew. My mother and my father were both only children, so I have no real cousins. But whatever I had, that’s who I saw. They were cousins.

Hold it a minute please. I need a drink. That’s a lot of talking. What else do you want to know?

Well, I would like to know what did you do in New York for these days that you were in New York and what happened after that?

In New York they showed me around. I walked myself silly over bridges and from this house to the next cousin’s house. I had a good time with my cousins my age. My aunts, as I called them, were good to me, trying to get me back on my feet because I guess I lost a lot of weight on this boat trip. Because we didn’t eat, we whoopsed.

Do you remember what neighborhood in New York you stayed in?

No. I don’t know.

And where did you go from New York? After you left New York, where did you go?

On a train to Chicago to my grandmother’s cousin who had money for me.

What was her name?

Her name was Tante Selig. She was born here and she never let me know that she had money for me, but she made sure that I knew enough English to get on the train and get a job.13Aunt Jenny Selig, née Hochstädter, who was born in Lampertheim in 1883, is the cousin of Lila’s grandmother Settchen Guckenheimer, née Hochstädter. Jenny emigrated to Chicago in 1911 with her husband Solly Spindel (1873-1924), her son Manfred (1909-1991) and her parents Moritz (1854-1927) and Sophie Hochstädter (1853-1945). In 1930 she married Sydney Hermann Selig (1873-1956). Her mother Sophie lived with her in the house at 7325 Constance Avenue in Chicago. Adolf Guckenheimer made contact with Jenny and Aunt Sophie at the beginning of 1938. They were to help get the children “out of ghostland” as quickly as possible and take Lila in. This was finally achieved in June 1940, when Lila received Jenny Selig’s affidavit for the USA in England and was able to leave for the USA. She lived in Aunt Selig’s household until her marriage to Leland Winter in 1943. I wasn’t here very long and I got a job at Carson Pirie Scott & Co. wrapping packages in the basement because my English wasn’t good enough to see the public.

What else do you remember about that time when you got to Chicago? Were your relatives kind to you? Were they worried about what happened to the rest of the family?

I don’t know. That was past. I was there already. Here today! And I met this boy from across the street that was going to the Chicago Law School, and he said, “You come along with me and I’ll get you a course where you can learn to talk English”.

What was this boy’s name?

This boy’s name was Leland Winter. I wound up marrying him. Yeah. [Laughs]

Did you learn enough English?

I learned enough English, yes.

What did you do after the university course?

When we got married, he was a law student. He graduated. He made the bar. While this was going on, I learned how to type and I typed his papers for him – whatever papers. We lived in Chicago, not far from his parents. His parents were very happy to see me because his mother comes from a little town not far from Gross-Gerau. His father came from Yugoslavia.

Do you remember which part of Chicago this was in?

Oh yeah, we lived on South Shore. We lived all right. We were poor. We lived with orange crates in the apartment, but we had enough.

Let’s talk about what you were doing in 19… What year were you married?

1942.

How long did your marriage last?

Thirty years. We had three kids and I divorced him when my youngest was 18 and we didn’t have to fight over the kids.

What are the names of your children?

My oldest was Laureen and she’s dead now. And then there’s Lance and then there’s Leslie. When these children were born, there were few other “Winter” children and they wanted us to name our children after this one and that one. We decided as long as his name was with an L, and my name was with and L, we named our children with L’s. We named them for my grandfather Ludwig and that settled it.

How many grandchildren do you have?

I have four.

What are their names and where are they? What do they do?

My youngest is Allison, and she’s leaving for college tomorrow; she’s going to Maine. Debates. Does it mean anything to you? My son has three children. There’s Elise, she’s 26. There’s Elena, she’s 24, and there’s Curtis who is 21. And I don’t have great-grandchildren. None of them are married.

Not yet?

No. I’m hoping.

Did you have a professional career? Did you have a work?

I worked wrapping packages. then I worked in a hat store. A very nice lady ran a hat store and I was the glorified errand girl. After that, I didn’t work for money for a couple of years. I did work for American Jewish Congress and the Drexel Home on the South Side. In the meantime, my grandmother was in New York and I brought her here and I had to find a place for her. She couldn’t live with me. I lived on the third floor and through the American Jewish Congress, I got her into this nice Drexel Home. but I had to work there volunteer, “Do this, honey”, you know. After a while, my husband got into other things and he wound up with the brick business. My husband was no businessman. He was a good lawyer, but no businessman. So I ran the business and I was lucky. I was female and it was strictly a man’s business. We bought the bricks as they came down from the buildings. There were crews that cleaned them up and stacked them and put them in railroad cars. It was up to me to ship them, to find customers to ship them to. The first customer we had was the Holiday Inn in Memphis.

What happened to your sister?

What happened to my sister? She met this nice boy in England and eventually I brought her here in early 1948. Her boyfriend came about the same time, but he had rich cousins in New York. Eventually he came here too and they got married and they settled in Chicago. They’re married 65 years now.

What is your sister’s name?

Ruth, yeah, and she’s a great-grandmother and she rubs it under my nose! [Laughs]

How, if any, your religious beliefs changed at all as a result of what happened to you?

My religious beliefs never changed. I was born Jewish, I was brought up Jewish, and even though I live in this very Christian retirement village, I’m still Jewish, and I let everybody know it.

Did your children follow your religious beliefs?

No. My daughter’s only child was Bar Mitzvah. She will be Jewish. My oldest granddaughter, my son’s oldest, will stay Jewish. The other two, they’ve got a Catholic mother.

You were married to your first husband for 30 years and you got divorced. Did you ever remarry again?

Yeah, I married Henry Williamson. He was the brother of the woman who taught my oldest daughter in Girl Scouts. Somehow I met him. They lived in Highland Park and they came to visit. He was happily married and I was married, and his wife got cancer and she died and I divorced my husband and somehow we got together. We were married 16 years.

What happened?

He had a heart attack on a cruise and died.

How long ago was this?

That was 1988.

Were you already in Florida at that time?

Oh, yes, yes!

You went to Germany, you said in 1990 or something like that?

I went to Germany in 1991 with a friend and it left me cold. What I saw was not what I remembered and what I remembered I wanted to remember and what I saw I could easily forget.

What do you mean?

Anti-Semitism is still there wherever you go. The person I traveled with also was military and we stayed at military bases, but we got out and we saw what goes on locally. You still saw swastikas in the bakery where we went and bought our lunch for the day. There was Anti-Semitism in certain areas. We were in Baden-Baden and they had some kind of demonstration. Definitely, Hitler Youths. I walked away.

Do you remember seeing some sort of demonstrations like that when you were a child?

I don’t remember that. That movement was very young then. I went back to Germany when the Germans invited my sister and me in 1988. This was a month after my husband died. But we went and we were treated royally, but the locals asked us to do things for their school. Actually it wasn’t the locals. It was the movement of the Germans that invited us. We should go to the schools and tell these kids that there was such a thing as the Holocaust, that my father was sent to a concentration camp. These kids just sat there with bare faces, couldn’t comprehend.

How old were these children?

These were seventh, eighth graders.

They were about as old as you were when you went to England. Do you remember the name of the organization in Germany that invited you and your sister?

No.

Which town was it? Was it in your hometown?

Where did we stay, we stayed in Frankfurt. Then we took a bus. We went to Gross-Gerau. That’s the city where we saw the kids in school and I saw some of the old buildings, you know, but I didn’t recognize any of the people there. That’s not when I went to see Gretchen. I went to see Gretchen with my friend that was in the military and we thought we could handle it. She told us when not to come because her son was home and he was strictly an SS boy. Now today, he’s my age.

He was SS during the war, during the Hitler time?

Yeah, but she asked us to come.

He was a member of SS?

Yeah.

Did she not want you to come because he was at home or something?

She wanted me to come. Not when her son was home. He was working. She was happy that I saw my grandmother’s credenza. Yeah. It was standing in her living room.

She was the one that used to be your grandparents’ maid?

Yeah.

And used to bring you food?

Yeah. She still lived in a little house where I remembered her to live, you know, all these years back.

Did you talk about your grandparents?

Vaguely. She told me that the last time that she saw them and I don’t remember when that was. I didn’t write it down. I was happy she saw them. And I got a hug and a kiss and we left. It was a matter of a half hour. Yeah.

Did her son during the war, did her son know that she came to visit your grandparents?

Who knows.

You don’t know that?

No.

That she seemed…, well obviously she was happy to see you, but did she seem emotional when you came?

No. No, cold, cold. I got a hug and a kiss, and that was about as far as she went. After all, she still felt like she was the maid. She was always the maid, even though my grandmother treated her royally. Even the maid in those days ate some of their meals with us. They didn’t eat in the kitchen. Kinderfräuleins for sure, but the maid, sometimes when it was a dinner that could be put on the table and she didn’t have to run and serve it. Right?

So the servants in your household, basically, on certain nights they were included in all of the family meals?

Yeah.

They should’ve felt like part of the family, you’re telling us?

Yeah.

Did you ever see the chauffeur that used to be your chauffeur?

No. No. He died some place along the way. Yeah. No, I never saw him.

But going back to the 1988 story that you were just saying right before, that there was an organization from – probably from Gross-Gerau – that invited you and your sister. How did they know to invite you? How did they find you?

My sister has a way of keeping in touch with everybody. I don’t know how she found them, but she said, “We’re invited – all expenses paid.” And they even invited my husband. And I said, “Sure. We’ll go.”

Have you ever met other people from Gross-Gerau whom you knew as a child that were Jewish?

No. My friends are from Frankfurt, and they’re the ones, in 1999 we were in New York and one of them made dinner and invited the other girls. I keep in touch with that one. Once – Rosh Hashanah, you know. And she tells me. It’s a phone call and we gossip for a half hour, and that’s it.

I’m just interested to find out if you know anything about the fate of these other people that were from Gross-Gerau whom were your grandparents friends from the Temple. You don’t know anything about anybody?

No. You have to remember my grandparents were a generation ahead of their parents, so there was very little contact. Their contact only was in Temple, you know. Yeah, they were older.

Is there anything that I’m leaving out that I haven’t asked you yet that you wanted to add about any of the experiences that you went through?

I have suppressed this for so many years that I wouldn’t talk about it when somebody asked me. I said, “Ah, forget it!” And even to my children, who know a little, not very much. I never really told them of how I grew up. They knew – my children met my grandmother when I brought her here. They went to visit her. Yeah.

Just once or have they kept up?

You try and get three kids together to visit their grandmother? Yeah. We did it. We brought her flowers, I would say, every couple of months.

She spoke German and your children,n did they speak German?

No. No. No.

So how were they able to communicate?

She said the right things in the right tones and she held their hands and she hugged them. And they knew that that was my grandmother. Yeah. I called her “Oma”, and today my grandchildren call me “Oma”.

What would you like your children, your grandchildren, everybody who is going to be your descendant, whom you’ve not met yet, and all of the other people that will ever watch this interview to know about how Holocaust affected you, or some sort of an outlook for the future that you would like to convey to them?

It was there. It existed. It’s not something that you can sweep under the carpet and forget. It was a time that existed, and it should be remembered for all those people who are not here anymore. How my children should know? Let them broadcast it that their mother was one of them, that she lived there and other people like me lived there, and somehow survived, and it should never ever happen again.

Thank you very much for letting us into your home and letting us interview you!

This has been Marina Berkowitz interviewing Lila Williamson about her experiences as a survivor of the Holocaust. This interview will be included as a valuable contribution to the oral visual history archives of the Holocaust Museum of Southwest Florida.

You did a good job! You did a wonderful job. Okay.

This is my calling card. My grandmother obviously had this made for me:

This is my mother and father and me on his automobile:

This is my parents all dressed up with furs and everything with some friends. I don’t know them:

These are pictures of my sister and me:

This is the first day I went to school in Gross-Gerau, which was a to-do. You got a big like something filled with candy, a „Tüte“ (bag):

That is us as kids:

This is pretty close before we left:

I would say that is the last picture of my grandparents. You’ve had enough.

Anmerkungen / Notes

- 1The event to which Lila refers and which forced the grandparents to leave Gross-Gerau was not Kristallnacht, but the so-called “boycott of Jews”, which was initiated by the SA throughout Germany on the night of March 31 to April 1 with attacks on Jewish businesses. As Lila will later explain in the interview, the Guckenheimer grandparents were so severely affected by this that they felt compelled to give up their family business and move to Frankfurt, where they hoped for more security in the anonymity of the big city and in the environment of a strong Jewish community. The move from Gross-Gerau to Frankfurt took place in September 1933.

- 2In German, the term “Macher” is used to describe a leader with assertiveness who takes action and puts his plans into practice.

- 3On the night of November 9-10, 1938, the so-called “Kristallnacht”, Lila’s father Otto and grandfather Ludwig Koch were arrested in Alzey. More than 30,000 Jewish men in Germany were deported to the Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. At this time, Lila’s grandparents Guckenheimer had already left Gross-Gerau and been living in Frankfurt for over 5 years. The event to which Lila refers here and which had prompted her grandparents to move to Frankfurt was not “Kristallnacht”, but the National Socialist call to boycott Jewish stores, which was initiated by National Socialist henchmen throughout Germany in the night from March 31 to April 1 with attacks on Jewish stores.

- 4This refers to Adolf Guckenheimer’s brother Ludwig, his wife Rosa and their two daughters Else and Luzie, who lived on the first floor of the Guckenheimer brothers‘ house. Both brothers sold their business and their house after the attacks. Adolf and his wife moved to Frankfurt with their granddaughters in the fall of 1933, while Ludwig decided to move to Wiesbaden with his family.

- 5In September 1936, Adolf and Settchen Guckenheimer moved into a rented apartment at Hammanstraße 4, about one kilometer from the Philanthropin. At the time, Hammanstraße was mainly inhabited by well-to-do Jews. It bordered a small municipal park, which was then called Eysseneckpark and was renamed Holzhausenpark after the war. Prior to this, after moving from Gross-Gerau, the Guckenheimer family lived in a rented apartment in Scheffelstrasse, which was in the immediate vicinity of the Philanthropin.

- 6Lila’s sister Ruth also attended the Philanthropin from September 1933 to spring 1936. There is a class photo with her from 1936. She then transferred to Dr. Heinemann’sche Mädchenpensionat in Frankfurt’s Westend in Mendelsonstraße, where her mother and grandmother Settchen had also previously been school girls (see interview with Ruth Veit, née Koch).

- 7From 1933 to 1935, Adolf Guckenheimer ran a small coal business in Frankfurt at Keplerstraße 7a until the Jewish population was banned from all participation in economic life.

- 8Otto Koch was arrested during „Kristallnacht“ on 9.11.1938 and deported to Buchenwald. He died there on December 2, 1938. His ashes were sent to his parents in Alzey. Lieselotte’s sister Ruth describes many of the details of her father’s arrest in her interview from 2011.

- 9The person in mention is Meta Hochstädter (1903-1985), the daughter of Lila’s great-uncle Karl Hochstädter (1876-1943), who is the brother of Settchen Guckenheimer.

- 10For Lila, the trauma of being a Holocaust survivor apparently blocked her memory of the end of her relationship with her grandparents for decades. Between 1940 and 1941, both the Guckenheimer grandparents and the Koch grandparents wrote her dozens of letters. For the Guckenheimr grandparents, the correspondence ended shortly before their deportation in November 1941. For the Koch grandparents, the correspondence ended at the same time when the USA entered the war. Many of the heartbreaking letters that Lila received have been preserved and can be read on this website.

- 11The person in mention is Aunt Laura Liebmann, née Koch, Thekla’s sister-in-law, who emigrated to New York in 1938.

- 12The person in mention is Luzie Levi, née Guckenheimer (1906-1962). She is the daughter of Lila’s great-uncle Ludwig Guckenheimer (1873-1937), the brother of Adolf Guckenheimer. Lila lived with Luzi’s family in the Guckenheimer family home in Groß-Gerau until 1933. In 1937, Luzi and her father fled to San Remo in Italy. They apparently tried to run a hotel there. But Ludwig Guckenheimer died in San Remo on 27.6.1937. Luzie escaped with her husband Julius Levi from Italy to New York.

- 13Aunt Jenny Selig, née Hochstädter, who was born in Lampertheim in 1883, is the cousin of Lila’s grandmother Settchen Guckenheimer, née Hochstädter. Jenny emigrated to Chicago in 1911 with her husband Solly Spindel (1873-1924), her son Manfred (1909-1991) and her parents Moritz (1854-1927) and Sophie Hochstädter (1853-1945). In 1930 she married Sydney Hermann Selig (1873-1956). Her mother Sophie lived with her in the house at 7325 Constance Avenue in Chicago. Adolf Guckenheimer made contact with Jenny and Aunt Sophie at the beginning of 1938. They were to help get the children “out of ghostland” as quickly as possible and take Lila in. This was finally achieved in June 1940, when Lila received Jenny Selig’s affidavit for the USA in England and was able to leave for the USA. She lived in Aunt Selig’s household until her marriage to Leland Winter in 1943.